Grandma Shirley and Me

In the wake of my grandmother’s death, many of the comments on my Facebook page offered this traditional Jewish condolence: “May her memory be a blessing to you.” Less than 24 hours after her passing, Grandma Shirley’s memory is already a blessing; a very well dressed, outspoken blessing. And it’s pushing a vacuum cleaner.

As a kid, my relationship with Grandma Shirley wasn’t so much a loving bond as it was a battle of wills: She willed me to behave, and I responded with willful disobedience. If Shirley was the hammer, I was that annoying little nail, forever slipping out of grasp and bending sideways—impossible to control.

Of seven grandkids, my sister and I were the only ones who didn’t grow up in Maryland. We lived in Texas, which, to my east coast Jewish family, was akin to living on the moon—only more desolate. Grandma tried making up for that distance the only way she knew how; she took us to the mall. For Grandma Shirley, shopping was a sacred ritual. For me, it was a form of mental and physical torture (depending on the style). But what I lacked in enthusiasm for shopping, I made up for with academic achievement.

Ours was a symbiotic relationship: I made As on my report card, and Shirley paid me for bragging rights. All flaws were concealed when she flashed those report cards and introduced my sister and me to the ladies at the club as her “Texan geniuses.”

Speaking of clubs, if shopping was Shirley’s religion, golf was her therapy. The term “grandma” conjures up images of gray-bunned ladies in flour-smudged aprons, but she had no interest in any of that business. Nothing about Shirley screamed “grandma.” She dressed in the latest fashions and always had a perfect pedicure inside her golf cleats.

Shirley did have her domestic vices though, including an unnatural attachment to her vacuum cleaner and a reputation for ramming it against bedroom doors on Saturday mornings. Family members near and far lived in fear of Shirley’s white glove visits, and we all let out a huge sigh of relief when her eyes finally started to go.

As proud as Shirley was of her pristine carpets, there was nothing she loved more than her grandchildren, which she often displayed by constructive criticism. Her focus varied from grandchild to grandchild, but with me, it was all about the hair. Our struggle over my hair was legendary: too long, to stringy, too messy, too frizzy, too weird. In her later years, we joked about how tough I was as a kid, but we never joked about the hair—she was serious about that shit. During one of my final visits before she started going downhill, the first words out of her mouth were, “Thank God you finally cut that mop off your head.” It took nearly half a century, but she was finally at peace with my hair.

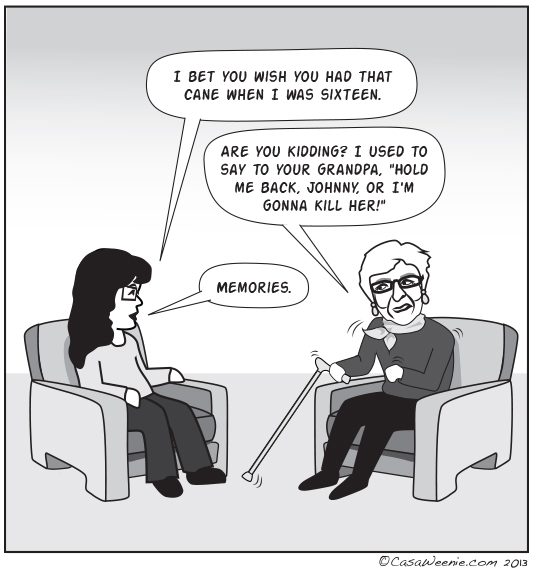

Of all the times I upset Grandma, the year I turned 16 was undoubtedly the worst. Keen on avoiding responsibility or repercussions after my parents discovered my more-than-recreational relationship with drugs, I fled 1,500 miles away to live with my grandparents in Silver Spring, Maryland. To say those were dark times for my family would be like saying the atomic bomb didn’t work well for the Japanese people. To put it mildly, I was a total nightmare.

It is truly impossible to overstate the scale of destruction I brought down upon everyone around me. Yet because of my grandparents’ intervention, I am here writing this today, rather than in a psychiatric unit wearing paper shoes and making keychains out of dental floss. Ultimately, Grandma’s love overpowered her instinct to murder me in my sleep, and somehow we both survived. (To be fair, the rest of my family and several sales clerks at Bloomingdales had the same struggle, so kudos to them.)

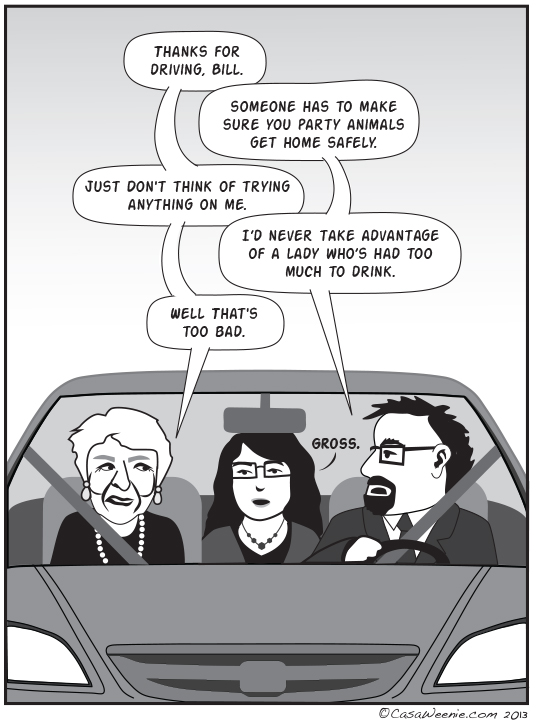

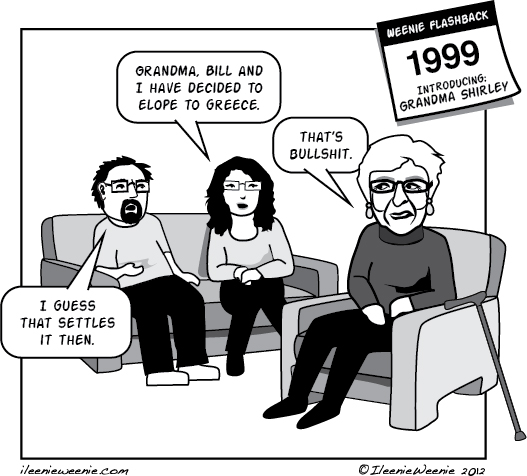

After the countless poor decisions I made, there was one that offset the entirety of my youth: marrying my husband, Bill. As the eldest grandchild, I liked to think I was her favorite (although the rest of the grandkids felt otherwise), but truth be told, Bill was her number one. He and Shirley shared a special bond, no doubt forged from shared Ilene-induced trauma. Combined with Bill’s natural tendency to go through life like an 85-year-old man, it was a match made in heaven.

I initially assumed Grandma wouldn’t approve of my husband’s religion or heritage, but what I failed to consider was my people’s awe of handymen. Back in the day, my beloved Grandpa Johnny owned a hardware store, so it should have come as no surprise that Bill’s ability to fix things would eclipse any cultural differences.

On her deathbed, Grandma could barely speak above a whisper, yet she somehow managed to gather up enough strength to ask me how the hell my husband put up with me for so many years. You had to admire the woman’s sense of timing.

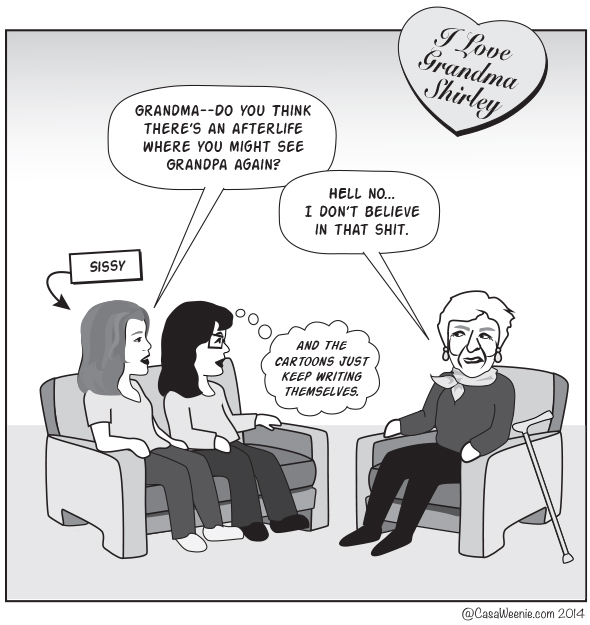

Shirley was an unsentimental broad with a quick wit and even quicker tongue. Most older folks start losing their filters somewhere along the way, saying anything they feel at any time. Shirley never had a filter to begin with, so were it not for the calendar, it was hard to tell she was aging at all.

Several years ago, Grandma was diagnosed with cancer. After one chemo treatment, she told her doctors to go to hell and never went back. In the end, she didn’t even die of cancer. Shirley’s death was a direct result of science’s inability to keep up with her. As sad as it was to see her go, I’m lucky to have had her in my life for 47 years. How many people can say that about a grandparent?

Grandma Shirley’s last whispered words to me were unexpected and perfect: “You’re a good girl, Ilene.” Blinking back my tears, a bittersweet smile was all I could manage in reply. “Nobody will ever love you like I do.”

Truer words were never spoken.